When most people think of souvenirs from Japan, they picture matcha-flavored KitKats or lucky cat keychains. But for CL, a 23-year-old on his second visit to Japan, the keepsake that stayed with him wasn’t something he found in a convenience store. Instead, it was a folded book filled with brushstrokes, red ink, and quiet ritual.

“I first found out about goshuin on TikTok,” he told me. “I was prepping for my trip and saw a video explaining what it was [basically shrine stamps] and it just stuck with me. I’ve always liked collecting things: watches, Pokémon cards… this felt like it belonged in that space too.”

Image Credit: Svetlana Gumerova | Unsplash

CL didn’t go to Japan planning to start a collection. But at Arakurayama Sengen Shrine, perched on a hillside near Mount Fuji, he noticed something that caught his attention. There was a queue of people lined up near a small counter. Behind it, shrine staff dressed in traditional white robes were carefully brushing black ink into small books. There was no fanfare, no loud conversation. Just a gentle, almost sacred kind of stillness. “It was beautiful,” he said. “They had a few stamp books on display too, and one of the covers really stood out. I bought it, and that’s how I started.”

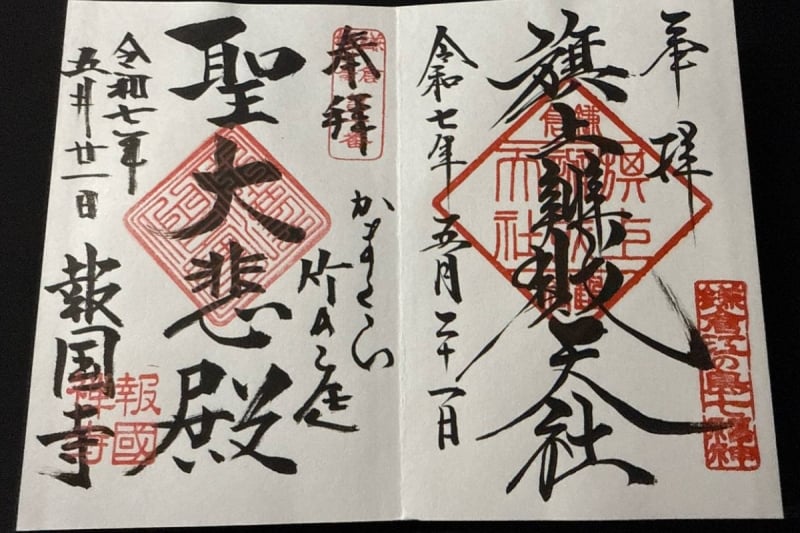

From CL’s goshuinchō

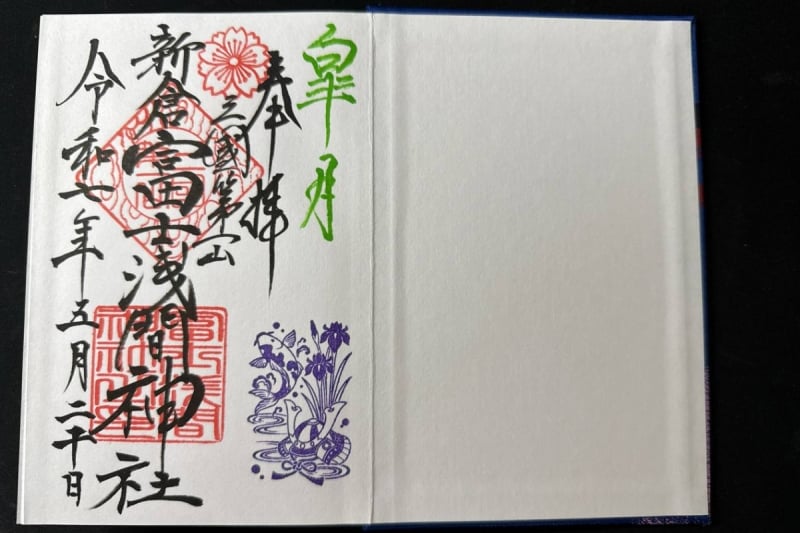

This stamp, known as a goshuin (御朱印), is one of the more quietly beloved aspects of Japanese shrine and temple visits. Most major religious sites offer them. It’s a red seal pressed into a special book called a goshuinchō, followed by the site’s name and the date of the visit, all handwritten in flowing calligraphy. Some are minimalistic, while others are elaborate, layered with smaller seasonal motifs, deity symbols, or stylised characters. But each one is unique to the site, making them a personalised marker of having been there.

At its core, a goshuin is both a record and a blessing. It’s a tangible imprint of your presence, but also a gesture of respect. Traditionally, pilgrims used goshuinchō to log their visits to sacred sites across long religious journeys (like the Shikoku 88 Temple Pilgrimage or the Kumano Kodo in Wakayama). Today, even more casual visitors engage in this practice, collecting goshuin as spiritual mementos, pieces of art, or simply beautiful souvenirs with meaning.

CL’s collection is still small. He describes himself as “definitely still a beginner”, but it’s already become something he looks forward to with each shrine visit. “It kind of feels like filling out a Pokédex,” he joked. “Every goshuin is different. You don’t know what it’ll look like until you get it, so it adds this layer of excitement to every trip.”

CL’s goshuinchō

He doesn’t have a grand plan for which sites to visit. Some collectors embark on themed trails, such as collecting goshuin from the seven lucky gods of fortune in Tokyo, or revisiting the same shrine each season to collect limited-edition stamps. For now, CL’s approach is more spontaneous. If a shrine is nearby, or if he happens to stumble upon one, he’ll go. But there is an important distintion to be made — this is not about ticking off a checklist as much as it is about paying attention, and being present.

What surprised him most, though, was how easy it is to get started. “Just make sure you’re there before the shrine office closes. Some places stop doing handwritten ones by 4:30PM. And always bring cash,” he said. “It usually costs around 300 to 500 yen. Just say ‘Goshuin onegaishimasu’ (Goshuin, please) and pass them your book open to a blank page.”

Image Credit: Forest Man | Unsplash

That said, there are a few subtleties first-timers should know. You’re encouraged to pray or offer respect before requesting a goshuin. Filming or photographing the writing process is frowned upon, because it is seen as a sacred ritual. And not all stamps are written directly into your book. Some sites offer pre-stamped sheets, especially during busy periods or late in the day. “I once missed the cutoff once by five minutes,” CL admitted. “I still got the stamp, but it was on a slip I had to paste in myself. Not the same.”

Even so, that goshuin still holds value. Each one in his book makes a moment tangible (whether it be a place, a time or a feeling), caught in calligraphy and red ink. “It’s low effort, but really satisfying,” he said. “Like, you’re just handing over your book, but when you get it back, it feels like something was made for you.”

In a country where ritual is often quiet and deeply embedded in daily life, goshuin collecting offers a way in. It’s personal but not performatively so. For travelers like CL, it offers something more lasting than just a photograph or a keepsake. His goshuinchō transforms into a paper trail of memory, and presence.

CL’s favourite goshuin

“I don’t know how long I’ll keep collecting,” he said, “but right now, it’s one of my favourite parts of being in Japan. And that first one from Arakurayama Sengen Shrine is still the most beautiful one I have.”

We live in a time where memory feels increasingly commodified. Photos become keepsakes for social media, and once they go public, they become curated, sometimes even monetised. Travelling itself can start to feel performative, like it’s about showing something off and proving how well-travelled one is.

Image Credit: grimnoire via Canva Pro

The act of collecting goshuin could be said to be a small resistance to such a phenomenon. It’s not mass-produced, and you can’t buy (real ones) online. You have to be there in person to ask, wait, then receive. And I think that’s part of why it resonates — maybe alongside other things like the rise of matcha, which, sure, is being commodified too, but also comes from a desire for calm, for slowness, for something more mindful. I just think if you do choose to start collecting goshuin, it’s worth remembering not to treat it like a checklist. Go with respect. Let it mean something, and try to catch yourself if you find yourself wanting to ‘complete’ a collection.